There’s currently a discussion at the W3C about how web apps should be installed from web browsers.

I won’t chronicle the whole twenty year long debate here, but suffice to say over the years browser vendors and OS makers have tried lots of different approaches.

The current solutions being considered for standardisation in the Web Applications Working Group are:

- The

beforeinstallpromptevent – An event on thewindowobject implemented in Chromium by Google (but not adopted elsewhere) which allows developers to intercept the browser’s own prompt to install the current app and provide their own UI - A

navigator.install()method – An explicit API implemented in Chromium by Microsoft and Google which allows developers to request installation of their app at any time (there is also a related cross-origin proposal for installing other apps) - An

<install>HTML element – A declarative solution (prototyped in Chromium) with a special button, whose content and presentation is controlled by the browser, which can be placed in a document to enable a user to install the current app

beforeinstallprompt

Pros:

- It gives the browser control over when an app can be installed, which may reduce noise slightly

- There is a trusted native browser user interface for installing apps

Cons:

- Unpredictable and confusing for developers. It’s an odd (though not unprecedented) API design to listen to an event which is emitted before something occurs and intercept it and call a method on the event object. Implementations of this event have so far been very unpredictable, with browsers using different heuristics to decide when to show an install app prompt.

- Likely to lead to nagging popups, banners or install buttons inside web apps trying to get users to install an app.

navigator.install()

Pros:

- An explicit, predictable API that developers can use when they choose

Cons:

- Likely to lead to annoying popups, banners or install buttons inside web apps trying to get users to install an app

- The UI is left down to developers so will be inconsistent, and could potentially even compete with the browser’s own prompts

<install>

Pros:

- Trusted native browser user interface for installing apps (though buried in web pages)

Cons:

- Likely to litter the web with install buttons

- Potentially problematic for some apps like games which use canvas or WebGL instead of the DOM

In my opinion all three of these proposed solutions risk littering the web with (at best) install buttons or (at worst) nagging popups and banners. The web is already plagued with interruptions like ads, paywalls and cookie consent banners and this would just add to the noise – further eroding the experience of web apps compared with native apps.

Another Way – Ambient Badging

In my opinion, the user interface for installing web apps should be trusted, consistent, easy to discover, but keep out of the way when it isn’t needed. It should feel equivalent to installing a native app (not a second class citizen), but also work to the unique strengths of the web rather than just imitating the model used by native app stores.

My view is that we already have a declarative solution for a web page to point to a web app that can be installed, and that’s a Web Application Manifest linked to using a manifest link relation in a link element:

<link rel="manifest" href="manifest.webmanifest">I believe Samsung coined the term “ambient badging” around 2017, but similar ideas had come before and after it, like Opera’s similar features and my own pinned apps proposal for Firefox OS in 2014 and ambient badging proposal for Fenix in 2019.

The basic idea is that the browser provides a subtle but immediately visible indication that the current web page is part of a web app that can be installed. In my opinion the best ambient badge for a web app is the web app’s own icon, but it could be a generic install button that appears somewhere in the browser chrome. The key thing is that there’s a clear indicator that the app can be installed, which doesn’t get in the way but isn’t buried deep inside a menu somewhere.

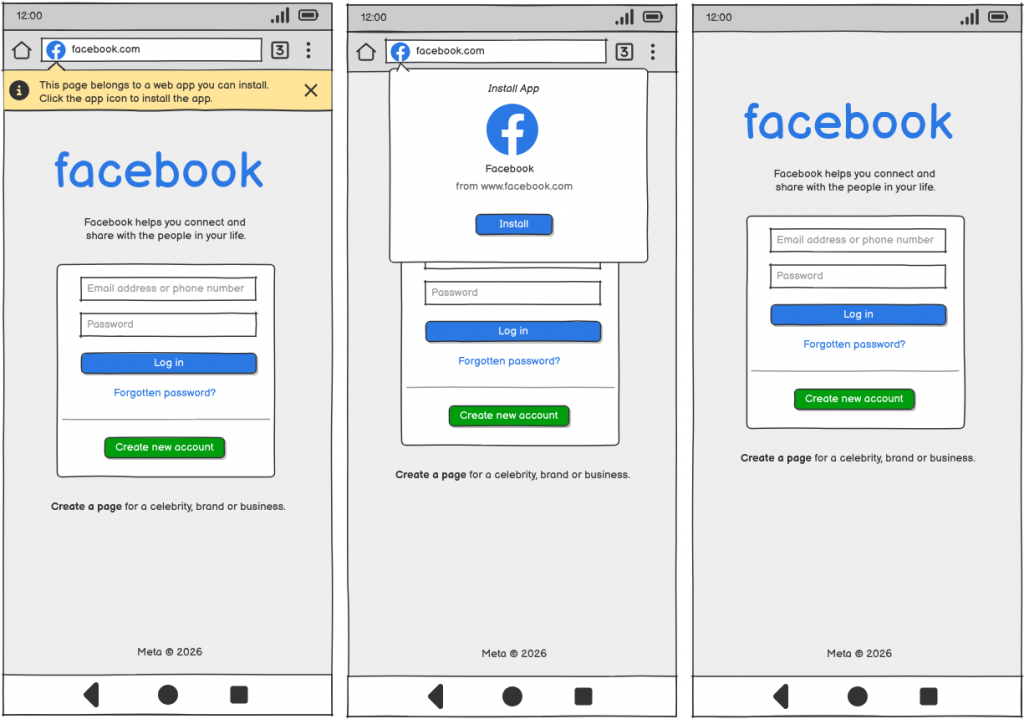

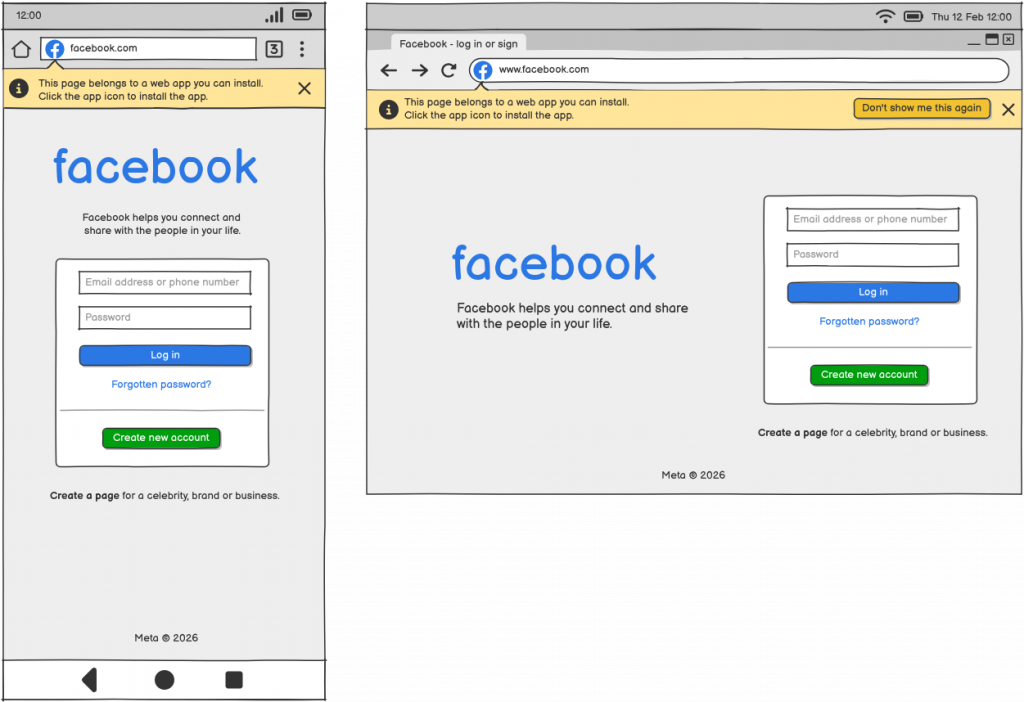

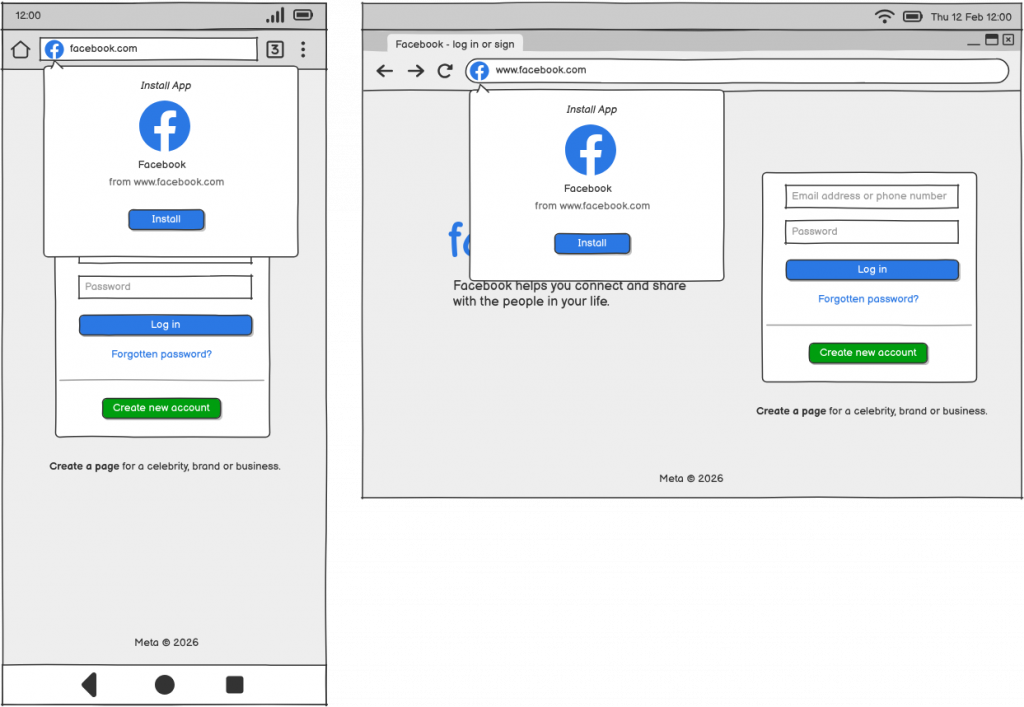

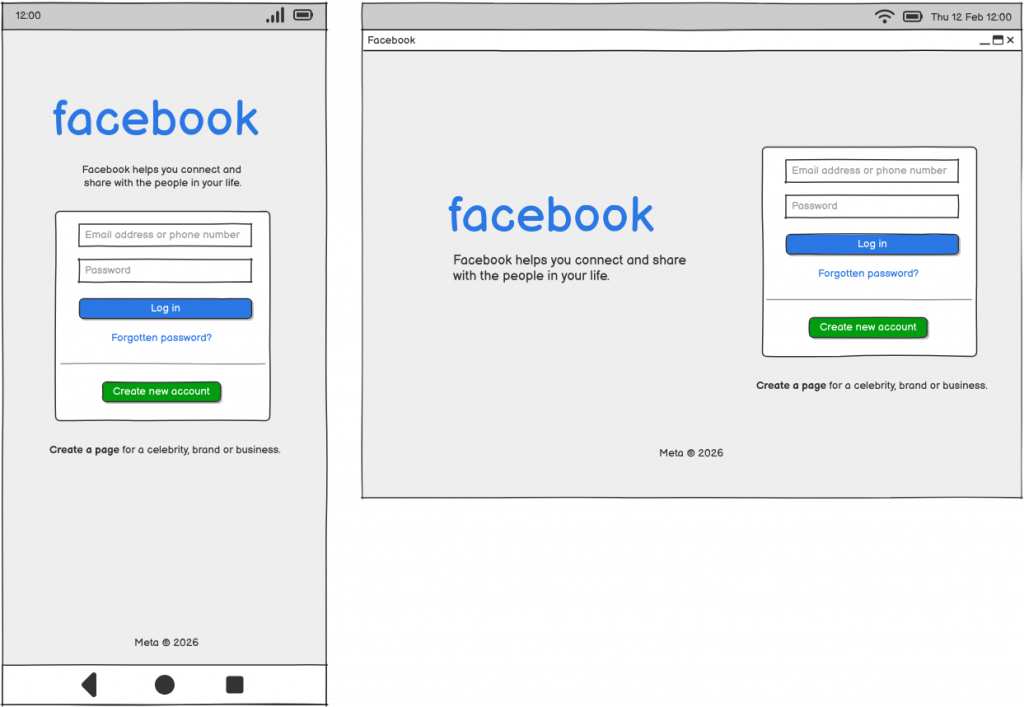

I’ve quickly created some example wireframes below to illustrate how this could look in existing mobile and desktop web browsers. When a user navigates to a page which links to a web app manifest (and the page falls within the navigation scope of that manifest), the browser displays a badge in the browser chrome indicating that there is an app that can be installed. Browsers can decide the criteria that a manifest needs to meet in order to show this badge (e.g. a valid manifest with a start_url and at least one icon), but it should be documented, consistent and predictable. The badge could potentially replace the site info icon if one is usually displayed, in order to reduce clutter.

The first few times a user navigates to a web page which links to a valid manifest it might be useful to show a hint which teaches the user about the feature (ideally displacing the viewport rather than obscuring it), so that they know where to find it. Note that the hint overlaps the URL bar so that it’s clear it is browser chrome and not content. Once the user has used the feature, or the prompt has displayed a certain number of times, or they have explicitly requested it not be shown again, the hint would no longer be displayed. The install app feature would then keep out of the way until it is needed (and could additionally be present inside an overflow menu for discoverability). Subtle animated cues could also help draw attention to the badge.

When the user clicks on the badge, they are presented with an app install dialog.

The app install dialog shows the name and icon of the app, and importantly the origin it is being installed from. Again note that the dialog overlaps the URL bar to show that it is browser chrome rather than content. In my opinion it’s important that the language used in this dialog matches the language used for installing native apps on that platform (i.e. “install” rather than “add to home” or “add shortcut”) so that it’s clear that this action is equivalent to installing a native app.

The app install dialog could be combined with other site information like a site info dialog if that helps to reduce clutter in the browser chrome.

Depending on the design of the particular operating system, once the user clicks the install button (and after any progress indicator has completed) they could either be navigated to a homescreen or app dock to show the new icon appearing, or the browser chrome could simply disappear as the manifest is applied to the browsing context to create an application context using the display mode specified in the manifest.

Once installed, web apps should ideally be treated as first class citizens on operating systems, appearing in lists of installed apps in app launchers and settings, and getting the same icon treatment as native apps.

Example Implementation

I’ve implemented the W3C Web Application Manifest specification a few times now, on Firefox OS and a prototype tablet, but most recently for the in-development Krellian OS smart building operating system.

Like Firefox OS, Krellian OS only runs web applications and the terminology used in the UI is to “pin” them. Pinning an app immediately transforms its browsing context into a standalone display mode and adds its icon to the app launcher.

Why only websites with manifests?

A change to the Editor’s Draft of the Web Application Manifest specification in February 2025 added a new informative definition of “installable web application” which includes the text “Any website is an installable web application.” This is to reflect a recent direction of browser vendors to treat all web pages the same whether they link to an app manifest or not. I don’t agree with this and think it’s actually inconsistent with the normative text of the specification, which says a web site can only become an “installed” web application if it links to a web application manifest.

Saying that any website is an installable web application also implies that all websites are web apps, which I don’t agree with. In my view, allowing any web page to be “installed” dilutes the concept of web apps and further erodes their perceived value and quality when compared with native apps. I think good web apps have certain important characteristics which differentiate them from websites, but as a minimum bar a website should need to self-declare as a web app by providing a web application manifest.

What about app stores?

Another feature that Microsoft in particular seem interested in is the installation of cross-origin or background documents. Both the navigator.install() and <install> solutions have been proposed as working cross-origin to install another web app, in addition to just the current web app. It appears Apple are not happy with that idea, but importantly the W3C TAG have also expressed concerns.

A key use case for this feature is to allow a website to act as an app store from which users can directly install web applications from other websites. Whilst this is something that we implemented back in the days of Firefox OS and the Firefox Marketplace, I’m not convinced it’s actually needed, or in fact in the interests of the web.

I personally think that rather than app stores, the web can benefit from web app directories with curated collections of apps including links that users can follow to immediately start using the app before deciding to install it through the native browser UI. I think this better leverages the unique strengths of the web, which are that web apps can be discovered and used immediately without needing to be installed, with installation being an optional additional step a user can take if they want to save the app to their device to use regularly.

The Caveat

I acknowledge that these ideas are not new, and they have been tried before. For this to become the de-facto solution for users to install web applications it requires all major browser vendors to be willing to surface web app installation much more visibly in their user interface. The solution is one of UI design using existing technologies, rather than prescribing a new API design in a specification. Unfortunately this is in conflict with bad incentives some browser makers have to bury web application installation deep inside an overflow menu.

In particular, I think it requires Apple to start seeing web apps as a complement to their curated proprietary app store, rather than a threat, and treat web apps as first class citizens on iOS and macOS. Otherwise I think we are doomed to a further degraded experience which makes the web suffer. I urge Apple to embrace Steve Jobs’ original vision of web apps being first class citizens on the iPhone.

I think browsers which visibly but subtly surface a trusted browser-native UI for installing web apps, which are treated as first class citizens on operating systems, would be the best outcome for the web.