Re-posted from Mozilla Hacks.

Boot to Gecko

As soon as the Boot to Gecko (B2G) project was announced in July 2011 I knew it something I wanted to contribute to. I’d already been working on the idea of a browser based OS for a while but it seemed Mozilla had the people, the technology and the influence to build something truly disruptive.

At the time Mozilla weren’t actively recruiting people to work on B2G, the team still only consisted of the four co-founders and the project was little more than an empty GitHub repository. But I got in touch the day after the announcement and after conversations with Chris, Andreas and Mike over Skype and a brief visit to Silicon Valley, I somehow managed to convince them to take me on (initially as a contractor) so I could work on the project full time.

A Web Browser Built from Web Technologies

On my first day Chris Jones told me “The next, highest-priority project is a very basic web browser, just a URL bar and back button basically.”

Chris and his bitesize browser, Taipei, December 2011

The team was creating a prototype smartphone user interface codenamed “Gaia”, built entirely with web technologies. Partly to prove it could be done, but partly to find the holes in the web platform that made it difficult and fill those holes with new Web APIs. I was asked to work on the first prototypes of a browser app, a camera app and a gallery app to help find some of those holes.

You might wonder why a browser-based OS needs a browser app at all, but the thinking for this prototype was that if other smartphone platforms had a browser app, then B2G would need one too.

The user interface of the desktop version of Firefox is written in highly privileged “chrome” code using the XUL markup language. On B2G it would need to be written in “content” using nothing but HTML, CSS and JavaScript, just like all the other apps. That would present some interesting challenges.

In the beginning, there was an <iframe>

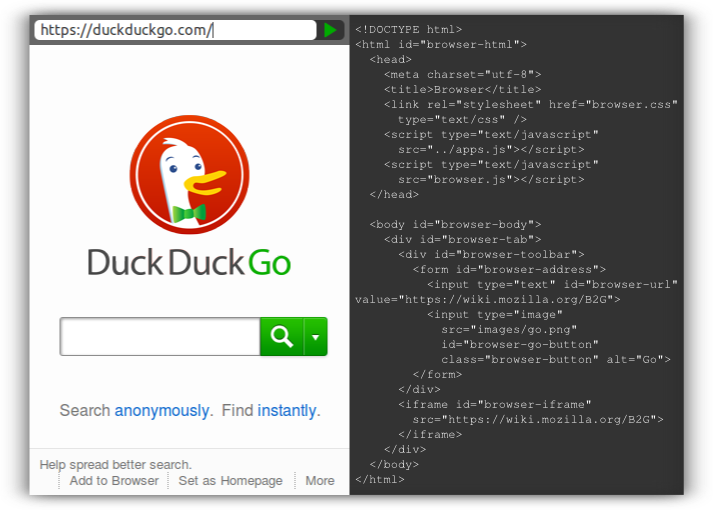

It all started with a humble iframe, a text input for the URL bar and a go button, in fact you can see the first commit here. When you clicked the go button, it set the src attribute of the iframe to the contents of the text input, which caused the iframe to load the web page at that URL.

First commit, November 2011

The first problem with trying to build a web browser using an iframe is that the same-origin policy in JavaScript prevents you accessing just about any information about what’s going on inside it if the content comes from a different origin than the browser itself. In particular, it’s not possible to access the contentWindow property and all of the information that gives access to. This policy exists for good reasons so in order to build a fully functional web browser we would have to figure out a way for a privileged web app to safely poke holes in that cross-origin boundary to get just enough information to do its job, but without creating serious security vulnerabilities or compromising the user’s privacy.

Another problem we came across quite quickly was that many web authors will go to great lengths to prevent their web site being loaded inside an iframe in order to prevent phishing attacks. A web server can send an X-Frame-Options HTTP response header instructing a user agent to simply not render the content, and there are also a variety of techniques for “framebusting” where a web site will actively try to break out of an iframe and load itself in the parent frame instead.

It was quickly obvious that we weren’t going to get very far building a web browser using web technologies without evolving the web technologies themselves.

The Browser API

I met Justin Lebar at the first B2G work week in Taipei in December 2011. He was tasked with modifying Gecko to make the browser app on Boot to Gecko possible. To me Gecko was (and largely still is) a giant black box of magic spells which take the code I write and turn it into dancing images on the screen. I needed a wizard who had a grasp on some of these spells, including a particularly strong spell called Docshell which only the most practised of wizards dare peer into.

Justin at the first B2G Work Week in Taipei, December 2011

When I told Justin what I needed he made the kinds of sounds a mechanic makes when you take your car in for what you think is a simple problem but turns out costing the price of a new car. Justin had a better idea than I did as to what was needed, but I don’t think either of us realised the full scale of the task at hand.

With the adding of a simple boolean “mozbrowser” attribute to the HTML iframe element in Gecko, the Browser API was born. I tried adding features to the browser app and every time I found something that wasn’t possible with current web technologies, I went back to Justin to get him to cast a new magic spell.

There were easier approaches we could have taken to build the browser app. We could have added a mechanism to allow the browser to inject scripts into the iframe and communicate freely with the content inside, but we wanted to provide a safe API which anyone could use to build their own browser app and this approach would be too risky. So instead we built an explicit privileged API into the DOM to create a new class of iframe which could one day become a new standard HTML tag.

Keeping the Web Contained

The first thing we did was to try to trick web pages loaded inside an iframe into thinking they were not in fact inside an iframe. At first we had a crude solution which just ignored X-Frame-Options headers for iframes in whitelisted domains that had the mozbrowser attribute. That’s when we discovered that some web sites are quite clever at busting out of iframes. In the end we had to take other measures like making sure window.top pointed at the iframe rather than its parent so a web site couldn’t detect that it had a parent, and eventually also run every browser tab in its own system process to completely isolate them from each other.

Once we had the animal that is the web contained, we needed to poke a few air holes to let it breathe. There’s some information we need to let out of the iframe in the form of events: when the location, title or icon of a web page changes (locationchange, titlechange and iconchange); when a page starts and finishes loading (loadstart, loadend) and when the security characteristics of the currently loaded page changes (securitychange). This all allows us to keep the address bar and title bar up to date and show a progress indicator.

The browser app needs to be able to navigate the iframe by telling it to goBack(), goForward(), stop() and reload(). We also need to be able to explicitly ask for information like characteristics of the session history (getCanGoBack(), getCanGoForward()) to determine which navigation buttons to display.

With these basics in place it was possible to build a simple functional browser app.

The Prototype

The Gaia project’s first UX designer was Josh Carpenter. At an intensive work week in Paris the week before Mobile World Congress in February 2012, Josh created UI mockups for all the basic features of a smartphone, including a simple browser, and we built a prototype to those designs.

Josh and me plotting over a beer in Paris.

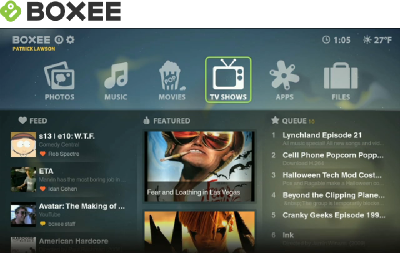

The prototype browser app could navigate web content, keep it contained and display basic information about the content being viewed. This would be the version demonstrated at MWC in Barcelona that year.

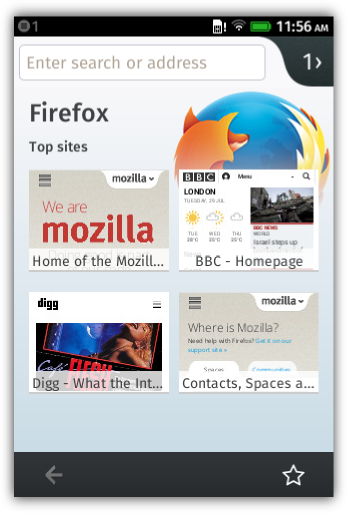

Simple browser demo for Mobile World Congress, February 2012

Building a Team

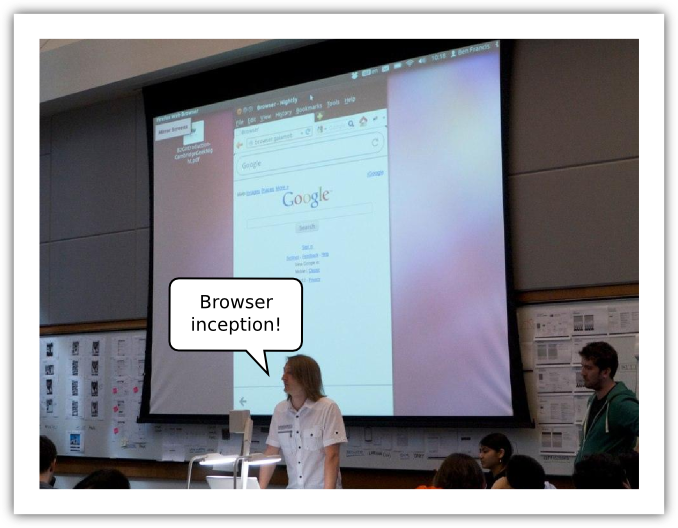

At a work week in Qualcomm’s offices in San Diego in May 2012 I was able to give a demo of a slightly more advanced basic browser web app running inside Firefox on the desktop. But it was still very basic. We needed a team to start building something good enough that we could ship it on real devices.

“Browser Inception”, San Diego May 2012

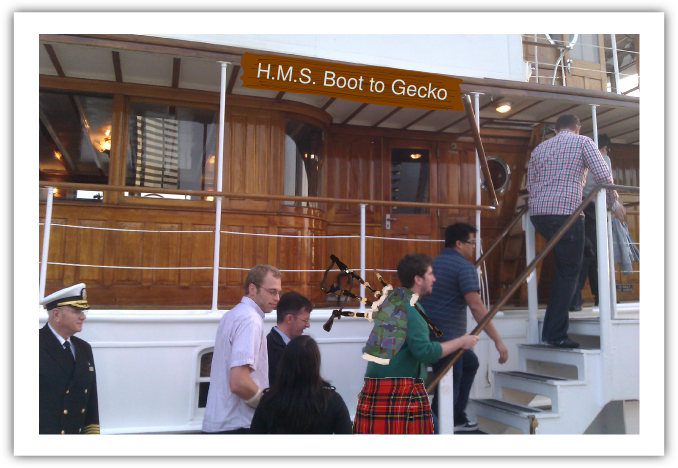

San Diego was also where I first met Dale Harvey, a brave Scotsman who came on board to help with Gaia. His first port of call was to help out with the browser app.

Dale Getting on Board in San Diego, May 2012

One of the first things Dale worked on was creating multiple tabs in the browser and even adding a screenshotting spell to the Browser API to show thumbnails of browser tabs (I told you he was brave).

By this time we had also started to borrow Larissa Co, a brilliant designer from the Firefox team, to work on the interaction design and Patryk Adamczyk, formerly of RIM, to work on the visual design for the browser on B2G. That was when it started to look more like a Firefox browser.

Early UI Mockup, July 2012

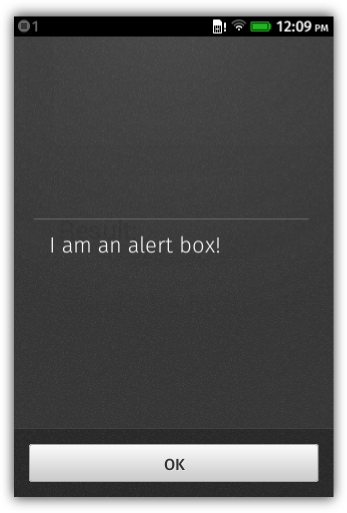

Things that Pop Up

Web pages like to make things pop up. For a start they like to alert(), prompt() or confirm() things with you. Sometimes they like to open() a new browser window (and close() them again), open a link in a _blank window, ask you for a password, ask for your permission to do something, ask you to select an option from a menu, open a context menu or confirm re-sending the contents of a form.

An alert(), version 1.0

All of this required new events in the Browser API, which meant more spells for Justin to cast.

Scroll, Pan and Zoom

Moving around web pages on web devices works a little differently from on the desktop. Rather than scroll bars or a scroll wheel on a mouse it uses touch input and a system called Asynchronous Pan and Zoom to allow the user to pan around a web page by dragging it and scrolling it using “kinetic scrolling” which feels like it has some physics to it.

The first implementation of kinetic scrolling was written in JavaScript by Frenchman and Gaia leader Vivien Nicolas, specifically for Gaia, but it would later be written in a cross-platform way in Gecko to unify the code used on B2G and Android.

One of the trickier interactions to get right was that we wanted the address bar to hide as you scrolled down the page in order to make more room for content, then show again when you scroll back to the top of the page.

This required adding asyncscroll events which tapped directly into the Asynchronous Pan and Zoom code so that the browser knew not only when the user directly manipulated the page, but how much it scrolled based on physics, asynchronously from the user’s interaction.

Storing Stuff

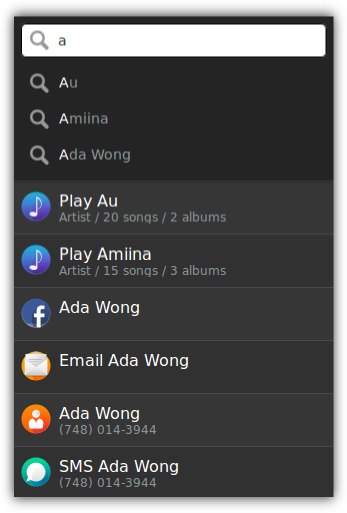

One of the most loved features of Firefox is the “Awesomebar”, a combined address bar, search bar (and on mobile, title bar) which lets you quickly get to the content you’re looking for. You type a few characters and immediately start to see matching web pages from your browsing history, ranked by a “frecency” algorithm.

On the desktop and on Android all of this data is stored in the “Places” database as part of privileged “chrome” code. In order to implement this feature in B2G we would need to use the local storage capabilities of the web, and for that we chose IndexedDB. We built a Places database in IndexedDB which would store all of the “places” a user visits on the web including their URL, title and icon, and store all the times the user visited that page. It would also be used to store the users bookmarks and rank top sites by “frecency”.

Awesomebar, version 1.0

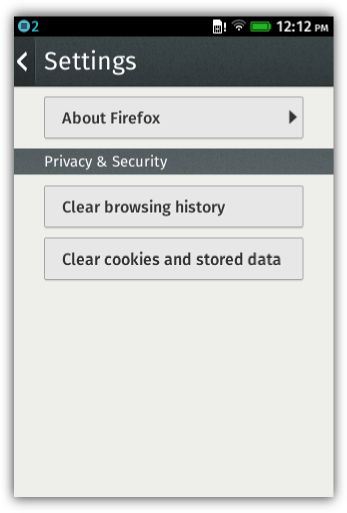

Clearing Stuff

As you browse around the web Gecko also stores a bunch of data about the places you’ve been. That can be cookies, offline pages, localStorage, IndexedDB databases and all sorts of other bits of data. Firefox browsers provide a way for you to clear all of this data, so methods needed to be added to the Browser API to allow this data to be cleared from the browser settings in B2G.

Browser settings, version 1.0

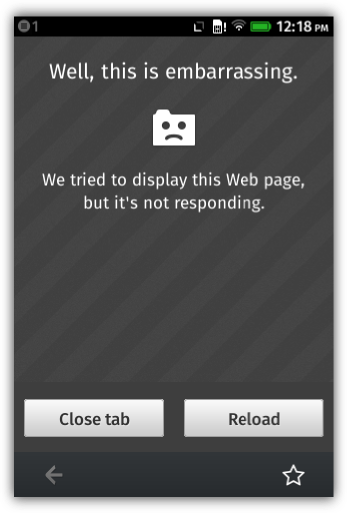

Handling Crashes

Sometimes web pages crash the browser. In B2G every web app and every browser tab runs in its own system process so that should the worst happen, it will only cause that one window/tab to crash. In fact, due to the memory constraints of the low-end smartphones B2G would initially target, sometimes the system will intentionally kill a background app or browser tab in order to conserve memory. The browser app needs to be informed when this happens and needs to be able to recover seamlessly so that in most cases the user doesn’t even realise a process was killed. Events were added to the Browser API for this purpose.

Crashed tab, version 1.0

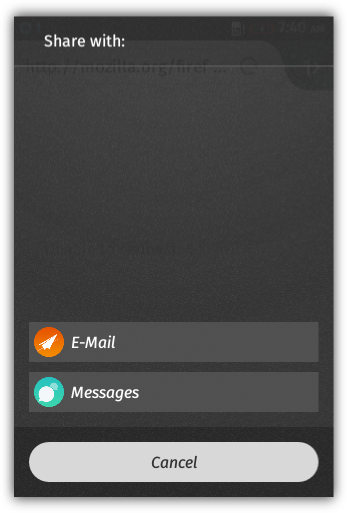

Talking to Other Apps

Common use cases of a mobile browser are for the user to want to share a URL using another app like a social networking tool, or for another app to want to view a URL using the browser.

B2G implemented Web Activities for this purpose, to add a capability to the web for apps to interact with each other, but in an app-agnostic way. So for example the user can click on a share button in the browser app and B2G will fire a “share URL” Web Activity which can then be handled by any installed app which has registered to handle that type of Web Activity.

Share Web Activity, version 1.2

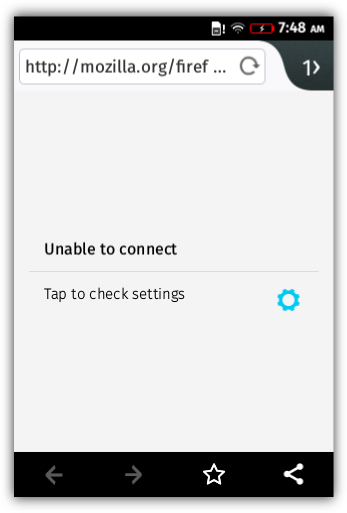

Working Offline

Despite the fact that B2G and Gaia are built on the web, it is a requirement that all of the built-in Gaia apps should be able to function offline, when an Internet connection is unavailable or patchy, so that the user can still make phone calls, take photos and listen to music etc.. At first we started to use AppCache for this purpose, which was the web’s first attempt at making web apps work offline. Unfortunately we soon ran into many of the common problems and limitations of that technology and found it didn’t fulfill all of our requirements.

In order to ship version 1.0 of B2G on time, we were forced to implement “packaged apps” to fulfill all of the offline and security requirements for built-in Gaia apps. Packaged apps solved our problems but they are not truly web apps because they don’t have a real URL on the Internet, and attempts to standardise them didn’t get much traction. Packaged apps were intended very much as a temporary solution and we are working hard at adding new capabilities like ServiceWorkers, standardised hosted packages and manifests to the web so that eventually proprietary packaged apps won’t be necessary for a full offline experience.

Offline, version 1.4

Spit and Polish

Finally we applied a good deal of spit and polish to the browser app UI to make it clean and fluid to use, making full use of hardware-accelerated CSS animations, and a sprinkling of Firefoxy interaction and visual design to make the youngest member of the Firefox browser family feel consistent with its brothers and sisters on other platforms.

Shipping 1.0

At an epic work week in Berlin in January 2013 hosted by Deutsche Telekom the whole B2G team, including engineers from multiple competing mobile networks and device manufacturers, got together with the common cause of shipping B2G 1.0, in time to demo at Mobile World Congress in Barcelona in February. The team sprinted towards this goal by fixing an incredible 200 bugs in one week.

Version 1.0 Team, Berlin Work Week, January 2013

In the last few minutes of the week Andreas Gal excitedly declared “Zarro Gaia Boogs”, signifying version 1.0 of Gaia was complete, with the rest of B2G to shortly follow over the weekend. Within around 18 months a dedicated team spanning multiple organisations had come together working entirely in the open to turn an empty GitHub repository into a fully functioning mobile operating system which would later ship on real devices as Firefox OS 1.0.1.

Zarro Gaia Boogs, January 2013

Browser app v1.0

So having attended Mobile World Congress 2012 with a prototype and a promise to deliver commercial devices into the market, we were able to return in 2013 having delivered on that promise by fully launching the “Firefox OS” brand with multiple devices on multiple mobile networks with a launch that really stole the show at the biggest mobile conference in the world. Firefox OS had arrived.

Mobile World Congress, Barcelona, February 2013

1.x

Firefox OS 1.1 quickly followed and by the time we started working on version 1.2 the project had grown significantly. We re-organised into autonomous agile teams focused on product areas, the browser app being one. That meant we now had a dedicated team with designers, engineers, a test engineer, a product manager and a project manager.

The browser team, London work week, July 2013

Firefox OS moved to a rapid release “train model” of development like Firefox, where a new version is delivered every 12 weeks. We quickly added new features and worked on improving performance to get the best out of the low end hardware we were shipping on in emerging markets.

Browser app v1.4

“Haida”

Version 1.0 of Firefox OS was very much about proving that we could build what already exists on other smartphones, but entirely using open web technologies. That included a browser app.

Once we’d proved that was possible and put real devices on shelves in the market it was time to figure out what would differentiate Firefox OS as a product going forward. We wanted to build something that doesn’t just imitate what’s already been done, but which plays to the unique strengths of the web to build something that’s true to Mozilla’s DNA, is the best way to experience the web, and is the platform that HTML5 deserves.

Below is a mockup I created right back towards the start of the project at the end of 2011, before we even had a UX team. I mentioned earlier that the Awesomebar is a core part of the Firefox experience in Firefox browsers. My proposal back then was to build a system-wide Awesomebar which could search the whole device, including your apps and their contents, and be accessible from anywhere in the OS.

Very early mockup of a system-wide Awesomebar, December 2011

At the time, this was considered a little too radical for version 1.0 and our focus really needed to be on innovating in the web technology needed to build a mobile OS, not necessarily the UX. We would instead take a more conservative approach to the user interface design and build a browser app a lot like the one we’d built for Android.

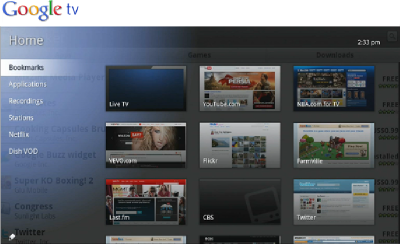

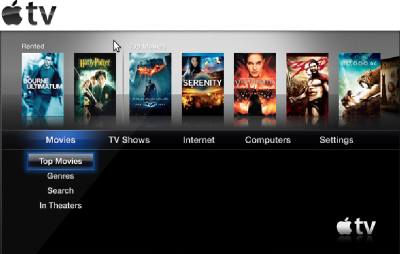

In practice that meant that we in fact built two browsers in Firefox OS. One was the browser app which managed the world of “web sites” and the other was the window manager in the system app which managed the world of “web apps” .

In reality on the web there isn’t so much of a distinction between web apps and web sites – each exists on a long continuum of user experience with a very blurry boundary in the middle.

In March 2013, with Firefox OS 1.0 out of the door, Josh Carpenter put me in touch with Gordon Brander, a member of the UX team who had been thinking along the same lines as me. In fact Gordon being as much of an engineer as he is a designer, had gone as far as to write a basic prototype in JavaScript.

Gordon’s Rocketbar Prototype, March 2013

Gordon and I started to meet weekly to discuss the concept he had by then codenamed “Rocketbar”, but it was a bit of a side project with a few interested people.

In April 2013 the UX team had a summit in London where they got together to discuss future directions for the user experience of Firefox OS. I was lucky enough to be invited along to not only observe but participate in this process, Josh being keen to maintain a close collaboration between Design and Engineering.

We brainstormed around what was unique about the experience of the web and how we might create a unique user experience which played to those strengths. A big focus was on “flow”, the way that we can meander through the web by following hyperlinks. The web isn’t a world of monolithic apps with clear boundaries between them, it is an experience of surfing from one web site to another, flowing through content.

Brainstorming session, London, April 2013

In the coming weeks the UX team would create some early designs for a concept (eventually codenamed “Haida”) which would blur the lines between web apps and web sites and create a unique user experience which flows like the web does. This would eventually include not only the “Rocketbar”, which would be accessible across the whole OS and seamlessly adapt to different types of web content, but also “sheets”, which would split single page web apps into multiple pages which you could swipe through with intuitive edge gestures. It would also eventually include a content model based around live apps which you can surf to, use, and then bookmark if you choose to, rather than monolithic apps which you have to install from a central app store before you can use them.

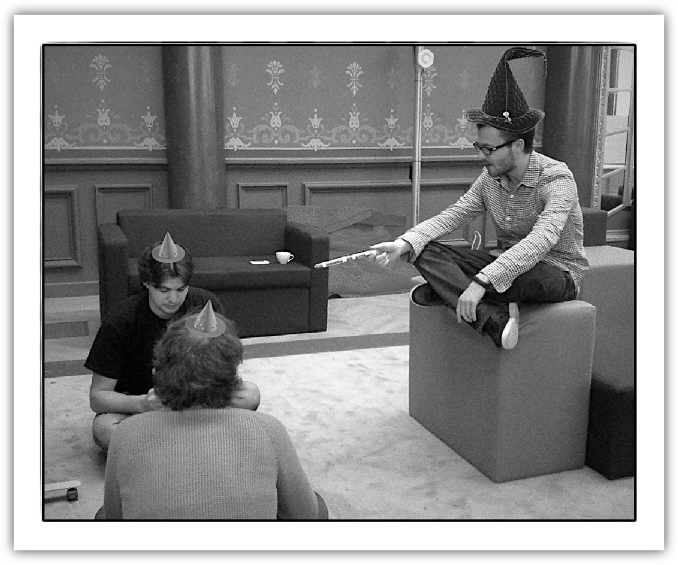

In June 2013 a small group of designers and engineers met in Paris to develop a throwaway prototype of Haida, to rapidly iterate on some of the more radical concepts and put them through user testing.

Haida Prototyping, Paris, June 2013

Josh and Gordon working in a highly co-ordinated fashion, Paris, June 2013

Wizards at work, Paris, June 2013

2.x and the Future

Fast forward to the present and the browser team has been merged into the “Systems Front End” team. The results of the Haida prototyping and user testing are slowly starting to make their way into the main Firefox OS product. It won’t happen all at once, but it will happen in small pieces as we iterate and learn.

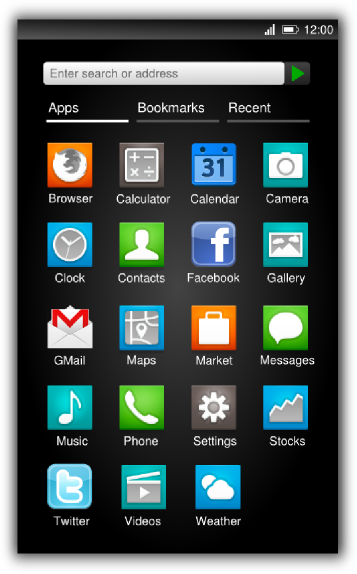

In version 2.0 of Firefox OS the homescreen search feature from 1.x will be replaced with a new search experience developed in conjunction with a new homescreen, implemented by Kevin Grandon, which will lay the foundations for “Rocketbar”. In version 2.1 our intention is to completely merge the browser app into the system app so that browser tabs become “sheets” alongside apps in the task manager and the “Rocketbar” is accessible from anywhere in the OS. The Rocketbar will adapt to different types of web content and shrink down into the status bar when not in use. Edge gestures will allow you to swipe between web apps and browser windows and eventually apps will be able to spawn multiple sheets.

UI Mockups of Rocketbar in expanded and collapsed state, July 2014

In parallel we see the evolution of web standards around manifests, packages and webviews and ongoing discussions around what defines the scope of an “app”.

Version 1.x of Firefox OS was built with web technologies but still has quite a similar user experience to other mobile platforms when it comes to installing and using apps, and browsing the web. Going forward I think you can expect to see the DNA of the web come through into the user interface with a unified experience which breaks down the barriers between web apps and web sites, allowing you to freely flow between the two.

Firefox OS is an open source project developed completely in the open. If you’re interested in contributing to Gaia, take a look at the “Developing Gaia” page on MDN. If you’re interested in creating your own HTML5 app to run on Firefox OS take a look at the “App Center“.