What is a web app? What is the difference between a web app and a web site? What is the difference between a web app and a non-web app?

In terms of User Experience there is a long continuum between “web site” and “web app” and the boundary between the two is not always clear. There are some characteristics that users perceive as being more “app like” and some as more “web like”.

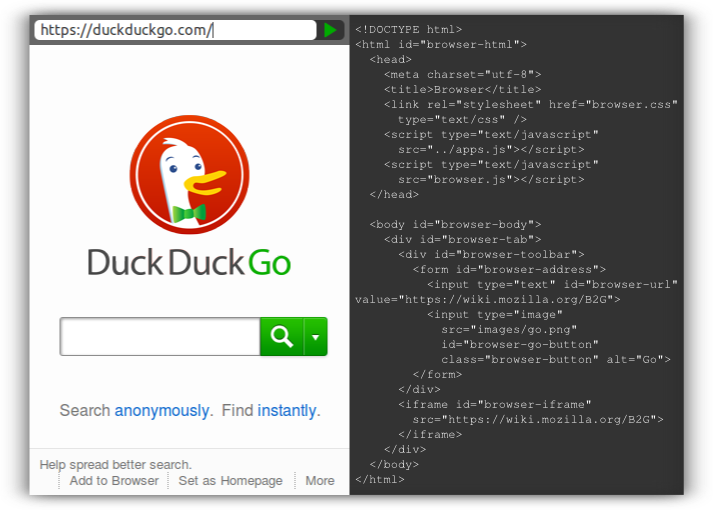

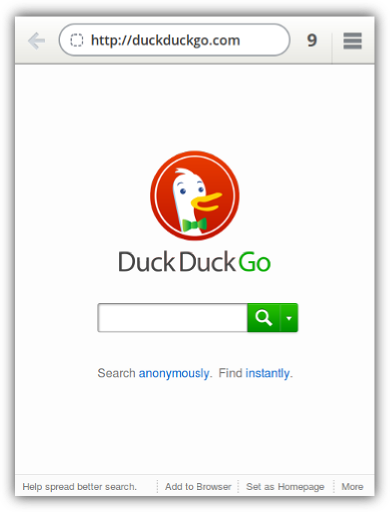

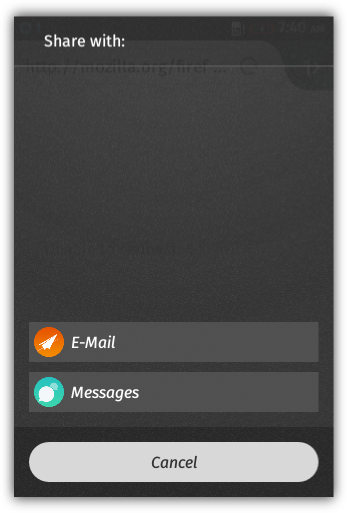

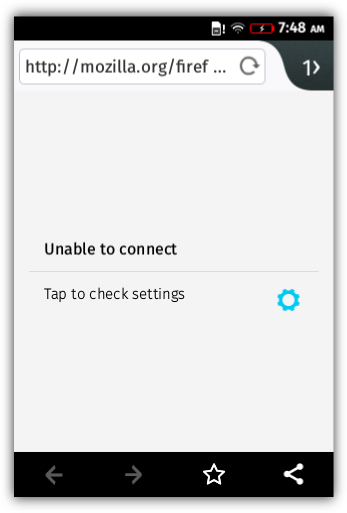

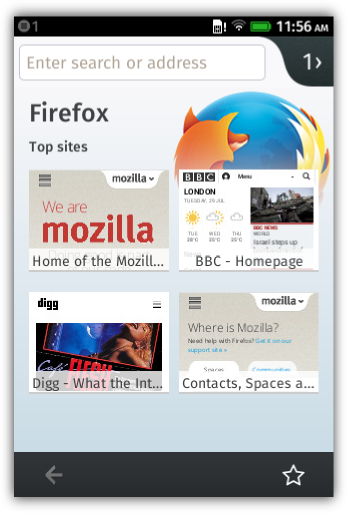

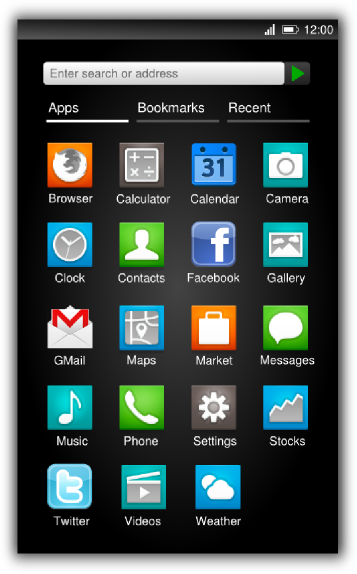

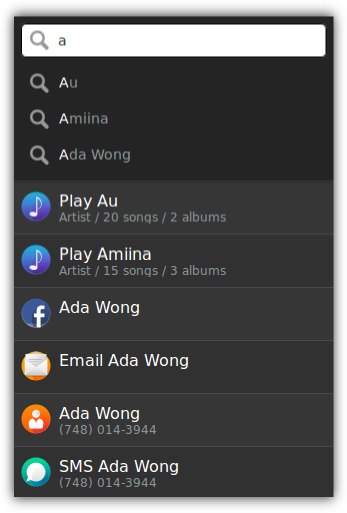

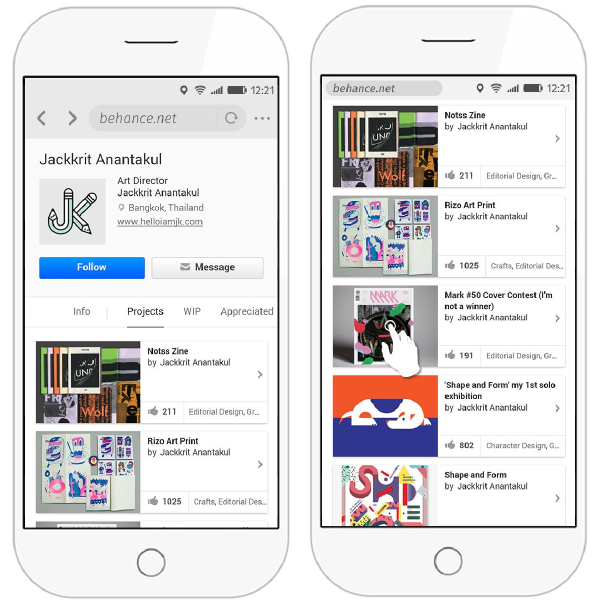

The presence of web browser-like user interface elements like a URL bar and navigation controls are likely to make a user feel like they’re using a web site rather than an app for example, whereas content which appears to run independently of the browser feels more like an app. Apps are generally assumed to have at least limited functionality without an Internet connection and tend to have the concept of residing in a self-contained way on the local device after being “installed”, rather than being navigated to somewhere on the Internet.

From a technical point of view there is in fact usually very little difference between a web site and a web app. Different platforms currently deal with the concept of “web apps” in all sorts of different, incompatible ways, but very often the main difference between a web site and web app is simply the presence of an “app manifest”. The app manifest is a file containing a collection of metadata which is used when “installing” the app to create an icon on a homescreen or launcher.

At the moment pretty much every platform has its own proprietary app manifest format, but the W3C has the beginnings of a proposed specification for a standard “Manifest for web applications” which is starting to get traction with multiple browser vendors.

Web Manifest – Describing an App

Below is an example of a web app manifest following the proposed standard format.

http://example.com/myapp/manifest.json:

{

"name": "My App",

"icons": [{

"src": "/myapp/icon.png",

"sizes": "64x64",

"type": "image/png"

}],

"start_url": "/myapp/index.html"

}

The manifest file is referenced inside the HTML of a web page using a link relation. This is cool because with this approach a web app doesn’t have to be distributed through a centrally controlled app store, it can be discovered and installed from any web page.

http://example.com/myapp/index.html:

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<head>

<title>My App - Welcome</title>

<link rel="manifest" href="manifest.json">

<meta name="application-name" content="My App">

<link rel="icon" sizes="64x64" href="icon.png">

...

As you can see from the example, these basic pieces of metadata which describe things like a name, an icon and a start URL are not that interesting in themselves because these things can already be expressed in HTML in a web standard way. But there are some other other proposed properties which could be much more interesting.

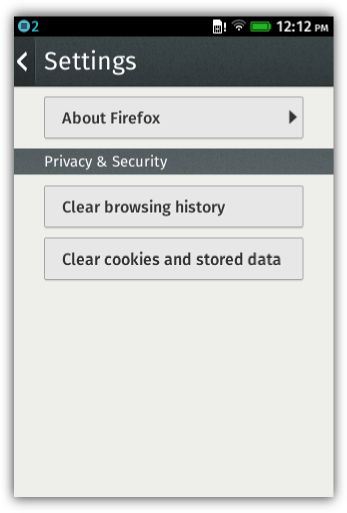

Display Modes – Breaking out of the Browser

We said above that one thing that makes a web app feel more app like is when it runs outside of the browser, without common browser UI elements like the URL bar and navigation controls. The proposed “display” property of the manifest allows authors of web content which is designed to function without the need for these UI elements to express that they want their content to run outside of the browser.

http://example.com/myapp/manifest.json:

{

"name": "My App",

"icons": [{

"src": "/myapp/icon.png",

"sizes": "64x64",

"type": "image/png"

}],

"start_url": "/myapp/index.html"

"scope": "/myapp"

"display": "standalone"

}

The proposed display modes are “fullscreen”, “standalone”, “minimal-ui” and “browser”. The “browser” display mode opens the content in the user agent’s conventional method (e.g. a browser tab), but all of the other display modes open the content separate from the browser, with varying levels of browser UI.

There’s also a proposed “orientation” property which allows the content author to specify the default orientation (i.e. portrait/landscape) of their content.

App Scope – A Slice of the Web

In order for a web app to be treated separately from the rest of the web, we need to be able to define which parts of the web are part of the app, and which are not. The proposed “scope” property of the manifest defines the URL scope to which the manifest applies.

By default the scope of a web app is anything from the same origin as its manifest, but a single origin can also be sliced up into multiple apps or into app and non-app content.

Below is an example of a web app manifest with a defined scope.

http://example.com/myapp/manifest.json:

{

"name": "My App",

"icons": [{

"src": "/myapp/icon.png",

"sizes": "64x64",

"type": "image/png"

}],

"start_url": "/myapp/index.html"

"scope": "/myapp"

}

From the user’s point of view they can browse around the web, seamlessly navigating between web apps and web sites until they come across something they want to keep on their device and use often. They can then slice off that part of the web by “bookmarking” or “installing” it on their device to create an icon on their homescreen or launcher. From that point on, that slice of the web will be treated separately from the browser in its own “app”.

Without a defined scope, a web app is just a web page opened in a browser window which can then be navigated to any URL. If that window doesn’t have any browser-like navigation controls or a URL bar then the user can get stranded at a dead on the web with no way to go back, or worse still can be fooled into thinking that a web page they thought was part of a web app they trust is actually from another, malicious, origin.

The web browser is like a catch-all app for browsing all of the parts of the web which the user hasn’t sliced off to use as a standalone app. Once a web app is registered with the user agent as managing a defined slice of the web, the user can seamlessly link into and out of installed web apps and the rest of the web as they please.

Service Workers – Going Offline

We said above that another characteristic users often associate with “apps” is their ability to work offline, in the absence of a connection to the Internet. This is historically something the web has done pretty badly at. AppCache was a proposed standard intended for this purpose, but there are many common problems and limitations of that technology which make it difficult or impractical to use in many cases.

A new, much more versatile, proposed standard is called Service Workers. Service Workers allow a script to be registered as managing a slice of the web, even whilst offline, by intercepting HTTP requests to URLs within a specified scope. A Service Worker can keep an offline cache of web resources and decide when to use the offline version and when to fetch a new version over the Internet.

The programmable nature of Service Workers make them an extremely versatile tool in adding app-like capabilities to web content and getting rid of the notion that using the web requires a persistent connection to the Internet. Service Workers have lots of support from multiple browser vendors and you can expect to see them coming to life soon.

The proposed “service_worker” property of the manifest allows a content author to define a Service Worker which should be registered with a specified URL scope when a web app is installed or bookmarked on a device. That means that in the process of installing a web app, an offline cache of web resources can be populated and other installation steps can take place.

Below is our example web app manifest with a Service Worker defined.

http://example.com/myapp/manifest.json:

{

"name": "My App",

"icons": [{

"src": "/myapp/icon.png",

"sizes": "64x64",

"type": "image/png"

}],

"start_url": "/myapp/index.html"

"scope": "/myapp"

"service_worker": {

"src": "app.js",

"scope": "/myapp"

}

}

Packages – The Good, the Bad and the Ugly

There’s a whole category of apps which many people refer to as “web apps” but which are delivered as a package of resources to be downloaded and installed locally on a device, separate from the web. Although these resources may use web technologies like HTML, CSS and Javascript, if those resources are not associated with real URLs on the web, then in my view they are by definition not part of a web app.

The reason this approach is commonly taken is that it allows operating system developers and content authors to side-step some of the current shortcomings of the web platform. Packaging all of the resources of an app into a single file which can be downloaded and installed on a device is the simplest way to solve the offline problem. It also has the convenience that the contents of that package can easily be reviewed and cryptographically signed by a trusted party in order to safely give the app privileged access to system functions which would currently be unsafe to expose to the web.

Unfortunately the packaged app approach misses out on many of the biggest benefits of the web, like its universal and inter-linked nature. You can’t hyperlink into a packaged app, and providing an updated version of the app requires a completely different mechanism to that of web content.

We have seen above how Service Workers hold some promise in finally solving the offline problem, but packages as a concept may still have some value on the web. The proposed “Packaging on the Web” specification is exploring ways to take advantage of some of the benefits of packages, whilst retaining all the benefits of URLs and the web.

This specification does not explore a new security model for exposing more privileged APIs to the web however, which in my view is the single biggest unsolved problem we now have left on the web as a platform.

Conclusions

In conclusion, a look at some of the latest emerging web standards tells us that the answer to the question “what is a web app?” is that a web app is simply a slice of the web which can be used separately from the browser.

With that in mind, web authors should design their content to work just as well inside and outside the browser and just as well offline as online.

Packaged apps are not web apps and are always a platform-specific solution. They should only be considered as a last resort for apps which need access to privileged functionality that can’t yet be safely exposed to the web. New web technologies will help negate the need for packages for offline functionality, but packages as a concept may still have a role on the web. A security model suitable for exposing more privileged functionality to the web is one of the last remaining unsolved challenges for the web as a platform.

The web is the biggest ecosystem of content that exists, far bigger than any proprietary walled garden of curated content. Lots of cool stuff is possible using web technologies to build experiences which users would consider “app like”, but creating a great user experience on the web doesn’t require replicating all of the other trappings of proprietary apps. The web has lots of unique benefits over other app platforms and is unrivalled in its scale, ubiquity, openness and diversity.

It’s important that as we invent cool new web technologies we remember to agree on standards for them which work cross-platform, so that we don’t miss out on these unique benefits.

The web as a platform is here to stay!